European agriculture is undergoing a very delicate situation that is threatening our food security. Over the last few years, our agrifood sector has been under strain due to extreme weather events like severe droughts and storms, high production costs, and the inflation crisis, as well as supply chain issues. Therefore, the Russian Federation’s unilateral withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Initiative could not come at a worse time.

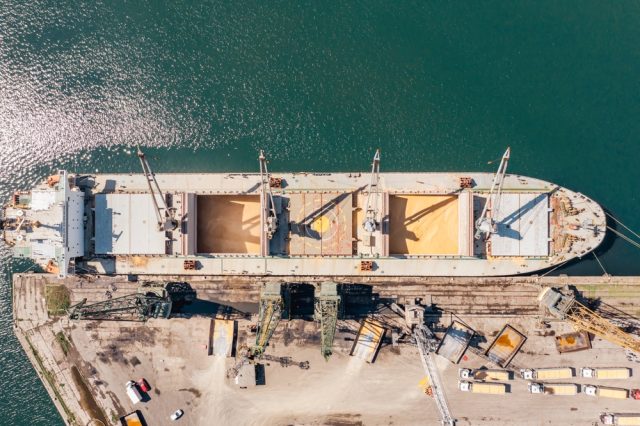

Following the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Ukrainian grain exports were virtually paralysed, as the Russian army captured important Ukrainian port cities on the southeastern coast like Kherson, Berdiansk, and Mariupol, while the largest ports in the southwest (Odesa and Mykolaiv) were blockaded and under artillery shelling.

Ukraine had been the ‘breadbasket’ of Europe and indeed much of the developing world. In 2021, Ukraine accounted for over 45% of sunflower oil exports, 12% of corn exports, and 9% of wheat exports. However, the war upended the agricultural market, and the month after the start of the invasion, Ukraine only exported 25% of its February export volumes. This had severe knock-on effects on the whole world and created a global food crisis.

This was the case for developing countries dependent on Ukraine for food imports, such as Egypt, Indonesia, Libya, and Pakistan. Even the UN’s World Food Programme, which feeds the world’s neediest, sources 40% of its wheat from Ukraine.

The war also had an impact on European food security and our agrifood industry, particularly for countries like Spain that are more dependent on Ukrainian exports.

Overall, the war caused a spike in global food prices that was unprecedented since the 1990s. According to FAO, the Food Price Index averaged 143.7 points in 2022, which is 14% higher than the 2021 average; while the FAO Cereal Price Index rose 17.9%.

In the EU, food inflation rates peaked at 18.2% in December 2022. Evidently, this had a knock-on effect on the entire agrifood supply chain and led to shortages and price increases of goods like flour to make bread and pasta, or food corn to feed livestock, which in turn affected meat and milk prices. These circumstances have impacted both production costs for producers along the food supply chain, as well as the prices paid by consumers.

A short-term solution was achieved when Russia and Ukraine signed the Black Sea Grain Initiative in July 2022 under the auspices of Turkey. Under the terms of this agreement, safe corridors were created in the Black Sea for Ukraine to be able to export grain, fertilisers, and other raw materials. This deal has allowed the export of about 32 million tonnes of Ukrainian wheat from non-occupied southern ports like Odesa. Russia has threatened to withdraw from the deal numerous times, but thanks to the involvement of the stakeholders, three extensions were secured. Nonetheless, Russia finally suspended its participation in July then the agreement expired, claiming that its demands hadn’t been met.

Russia’s withdrawal will pose significant challenges to the global, and indeed European, agrifood markets. The EU Agriculture Commissioner, Janusz Wojciechowski, has assured that “we are ready to export by solidarity lines almost everything that Ukraine needs to export”. However, these solidarity lanes that were put in place in May of 2023 have their limitations.

Firstly, logistically they don’t have the same capacity as maritime transport to channel Ukrainian exports due to their sheer volume. Indeed, before the war, over 90% of grain exports were shipped form the ports of Kherson, Odesa and Mariupol. Redirecting exports to ‘solidarity lanes’ and other routes has already, and will continue to, pose a logistical challenge.

And secondly, the solidarity lanes have faced resistance from Central and Eastern European Member States. The transit of Ukrainian food exports has posed a challenge for bordering countries like Poland, Slovakia or Romania because some of the produce has ended up getting stuck and flooding local markets, in turn undercutting local prices and fuelling resentment from domestic producers. This has led to intense farmer protests and unilateral import bans in these countries. To mitigate these circumstances, last June the European Commission approved an additional support package of 100 million euros for the affected countries.

Nonetheless, the Russian withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Initiative will put additional pressure on the ‘Solidarity Lanes’ and possibly increase conflict with Central and Eastern European Member States. Indeed, Polish Agriculture Minister Robert Telus has already warned that if it becomes necessary and the EU doesn’t extend the temporary restrictions on certain Ukrainian exports, Poland will impose a unilateral ban.

In any case, Europe’s agrifood sector will suffer in the months ahead due to the disruption of agricultural supplies. During the informal Council meeting of Agriculture Ministers in July, the Spanish Presidency of the Council highlighted that the EU’s agriculture reserve is “exhausted” due to the 330-million-euro emergency aid package that the Commission approved in June. This means that the EU will have it difficult to support and shield the agrifood sector’s increased production costs in the months ahead, and we will no doubt see shortages, supply chain issues, and aggravated inflation of agrifood prices.

Spain, which is the second-largest destination of Ukrainian grain after China, is an illustrative case study to reflect the severe impact that the suspension of the Black Sea Grain Initiative will have on the European agrifood industry. Since August 2022, 18.2% of Ukrainian grain exported across the Black Sea went to Spain, and this country sourced 44.2% of its cereal from Black Sea exports. Already before the war, Spain imported 60% of its sunflower oil, 30% of its corn, and 17% of its wheat from Ukraine.

The Ukraine War has therefore had a significant impact on Spanish agriculture and inflation more generally, so it serves as a useful window into what might happen in the coming months. In August of 2022, flour prices had increased 40% compared to 2021, while the Spanish agricultural association UPA estimates that in 2022, due to the Ukraine War and droughts, farmers had to pay 47% more for livestock feed.

These price increases for raw materials in turn have had a palpable impact on food prices paid by consumers. In the fourth quarter of 2022, the interannual inflation rate for all food types was 14.2% in Spain and 13.5% in the Eurozone. It has been especially marked in the case of bread and cereals (for which we are more dependent on Ukraine), with inflation rates of 19.3% in Spain and 16.9% in the Eurozone.

Policymakers, therefore, face an important challenge in responding to this complicated economic situation. But every cloud has a silver lining, and perhaps it serves as a wake-up call for Brussels to start prioritising food sovereignty and security, rather than destroying our agriculture to meet green targets set by unaccountable supranational institutions like the WEF.

Subscribe

Subscribe