There is no question about the immorality of slavery. The very idea that one person can own and abuse another one is abhorrent to modern man. But some claims about slavery are not about morality, but about facts, for example a recent statement by London Mayor Sadiq Khan ‘that our nation and city owes a large part of its wealth to its role in the slave trade’. It is also plausible that colonialism is wrong, if what is meant by it is the conquest by a mighty nation of some weaker ones and then ruling them against the wishes of their members. But again, some claims about colonialism are not about morality, but about facts, for example the assertion by left-wing journalist Owen Jones that the ‘blood money of colonialism enriched western capitalism’. In a short and readable book published this year, Dr. Kristian Niemietz of the London Institute of Economic Affairs presents convincing evidence that those two claims are false. His conclusion is: ‘Colonialism and the slave trade were, at best, minor factors in Britain’s and the West’s economic breakthrough, and quite possibly net lossmakers.’

Slavery Unproductive

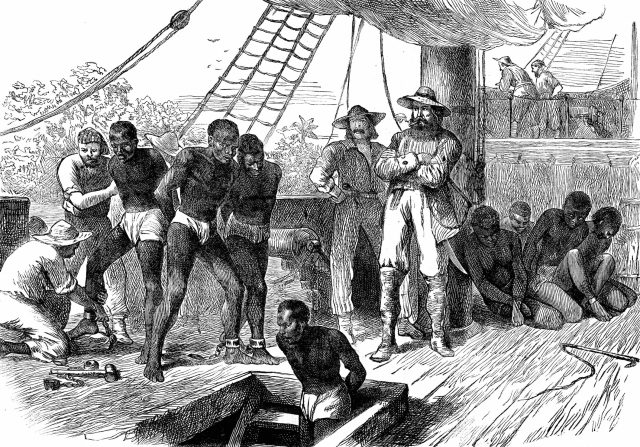

In 1776, Adam Smith pointed out in the Wealth of Nations that slavery was not likely to be productive because slaves had no incentive to exert themselves or to reveal and develop any special skills: ‘The experience of all ages and nations, I believe, demonstrates that the work done by slaves, though it appears to cost only their maintenance, is in the end the dearest of any.’ Niemietz agrees and asks a lot of pertinent questions about Britain’s transatlantic slave trade. How big were the profits derived from slavery, compared to the overall size of the British economy, or British investment? Did those private profits exceed the cost to the taxpayer? Could the plantations in America have existed without slavery, on a smaller scale?

Modern research shows that profits from the slave trade were about equivalent to just under 8 per cent of Britain’s total investment. This means that even if the slave traders were unusually astute investors, they would not have contributed much to Britain’s total investment. The research also shows that sugar plantations, usually depicted as bastions of enslavement, at their peak contributed a mere 2.5 per cent to the value of the British economy. This was less than, say, sheep farming did, but as Niemietz remarks nobody asserts that sheep farming financed or accelerated the industrial revolution.

Moreover, the maintenance of slavery was far from being costless, for example the defence of the Caribbean islands where sugar plantations were located. At the time of the slave trade, Great Britain retained a much larger military force than other European countries, and the British population was taxed heavily. Niemietz concludes: ‘The gains were small relative to the size of the British economy, and they cannot have explained more than a small share of total investment. Once we subtract the fiscal cost, the net gains may well have been negative.’ Niemietz doubts however that the plantation economy would have thrived without slavery. Probably its only positive contribution to the European economy was that for a period it brought down the price of sugar, coffee and other tropical products from the level that would have been reached by a free market (with hired labour instead of slaves).

No Gain for the Colonisers

At first sight, colonialism seems not as inherently evil as slavery. It is conceivable, although perhaps not likely, that a civilised nation would conquer a land populated by savage tribes, rule it wisely, educate the people and gradually civilise it. But leaving aside morality, could colonialism have been profitable for the colonisers? Adam Smith did not think so, and surprisingly Otto von Bismarck agreed with him. ‘The supposed benefits of colonies for the trade and industry of the mother country are, for the most part, illusory. For the costs involved in founding, supporting and especially maintaining colonies,’ Bismarck observed, ‘very often exceed the benefits that the mother country derives from them, quite apart from the fact that it is difficult to justify imposing a considerable tax burden on the whole nation for the benefit of individual branches of trade and industry.’

Niemietz discusses four colonial empires, the British, French, German, and Belgian. He points out that the exploitation of colonies cannot have been a significant factor in British industrialisation and wealth. Before the advances in container shipping, transport logistics, and communication technologies which have enormously facilitated international trade, the bulk of Britain’s economic activity was domestic. Even then, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Britain’s most important trading partners were her European neighbours, not her colonies. Research shows that most of British investments were financed from domestic savings and intra-Western trade. Moreover, the cost of acquiring and keeping colonies must be balanced against any possible gain. Niemietz concedes that empires may encourage trade within their borders, but some trade outside would have occurred anyway. His conclusion, based on expert opinion, including that of left-wing historians, is that some strategically placed groups may have benefitted from the British Empire, but that it is doubtful that the net total gain was larger than the net total cost. In the French case, it seems however that the empire was broadly self-funding. Thus, France was neither better nor worse off because of her colonial empire. In the German case, the record confirms Bismarck’s belief that the cost of the colonies was higher than the gain.

Loss for the Colonised

The only colonial empire where the gain for the coloniser clearly seems to have been greater than the cost was the Belgian one. But this was a special case for two reasons, Niemietz observes. The Belgian treasury spent almost nothing on the colonies, and they included territories rich in natural resources: some parts of Congo were almost like a modern Kuwait. The Belgian Empire certainly was colonialism at its worst.

While mostly there was no significant net gain for the colonisers, it is plausible to assume that often the colonised suffered a loss. One reason was that colonial rule was usually authoritarian, with little inbuilt restraints. After independence, local elites took over this unrestrained power. Exploitation by foreigners was replaced by exploitation by a ruling class (except in settler states like Canada, Australia, and New Zealand where institutions like those in Great Britain emerged). Another reason was that at least in Africa the slave trade, with captives of war being sold to Europeans, had a detrimental effect because it brought about social and ethnic fragmentation which in turn impeded economic progress.

Some Further Observations

One asset of Niemietz’ book is its brevity. I cannot however resist adding a few observations. The case of Iceland seems to confirm the author’s findings. In late eighteenth century, some prominent Britons proposed that Great Britain should seize Iceland, then in effect a Danish colony. The British authorities studied the proposal and concluded that it would be relatively easy to occupy Iceland, but costly to keep it. Consequently, they rejected the proposal. In the nineteenth century, Denmark spent roughly double the amount of money on Iceland what she received from her. It is also an interesting fact that today, the three richest European countries, Switzerland, Norway and Iceland, were no colonial powers.

Secondly, in the twentieth century the Soviet Union reintroduced slavery in the notorious labour camps, the Gulag. Those camps were probably not productive in the long run, for the reasons Adam Smith listed. They may have been even less productive than the plantations in the South of the United States, the Caribbean and Brazil, because the Gulag inmates were not bought at a market price so that their ‘owner’—the Soviet Communist Party—had little incentive to treat them well. The Soviet Union also established a colonial empire although it was not called by that name: it controlled a lot of vassal states and exploited them mercilessly.

A third observation is that slavery began earlier and ended later in the Arab countries than in the West, whereas it does not seem to have created any wealth there. Even in remote Iceland, Arab pirates came in 1627 and captured hundreds of people whom they subsequently sold in slave markets in North Africa. It is estimated that in total the Arabs enslaved more than one million white Europeans and about seven million black Africans, whereas between ten and twelve million Africans were forcibly brought to the Americas.

A fourth point is about compensation. If we accept, for the sake of argument, that whole groups should be regarded as victims of injustice and that they should therefore be compensated, then arguably traditional principles of insurance should apply. This implies that the compensation should make them as well off as they would have been, had they not become victims of injustice. Thus, descendants of slaves in the United States should be ensured the same living standard as they would have had if their forefathers had remained in Africa and not been captured by fellow Africans and sold to Europeans. But the irony is that this living standard would on average be much lower than those descendants of slaves now enjoy in the United States.

Fifthly, it is quite telling that the population of one of the last colonies, Hong Kong, would have preferred to stay under British rule rather than be handed over to China in 1997. While colonialism may often have inflicted more cost than gain on the colonised, this was certainly not so in Hong Kong. The well-written and moving novels about colonialism, such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and E. M. Forster’s Passage to India, only offer one part of the truth. There are others, as Niemietz’ book and the example of Hong Kong demonstrate.

Subscribe

Subscribe