It is a well-known historical fact that the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which had maintained a certain stability by keeping an heterogeneous number of Central and Eastern European people with their respective ethos under a single crown inherited from long before, was first eroded by the aggressions of the Second Reich and then finally obliterated by the winning allies of World War I.

The history of those people after most of them managing to get rid of the yoke of socialism is equally heterogeneous. From the relatively early EU accession of Greece in 1981 to the Yugoslav Wars at the end of the previous century, the disparity among different nations is not lesser now than it was by the fall of the last Habsburg.

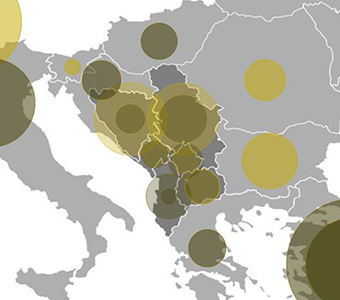

No wonder then that the energetic picture of the zone is very diverse, as well. Against this scenario, does the uniformising “Green Deal” make any sense, at all?

Let us analyse some facts. Mrs. Von der Leyen’s star plan -for it is a plan conceived by her team rather than a deal- requires a budget of €4 trillion for the decarbonisation of the energy industry. But many of the Balkan countries offer excellent opportunities for carbon energy, such as Albania’s Patos-Marinza field for oil or Romania being the second gas producer in the European Union. Why waste them?

This would surely confirm the dependence on Russian energy, with its indirect sweeping effect on inflation, but also on international relations. Serbia, to take one of the clearest cases, is completely dependent on Russia for natural gas.

An increase in investments in the Balkans gas distribution network would be very sensible. In part, the European Commission has corrected itself, by publishing in November 2021 that it would include 20 gas transmission and storage developments out of 98 projects of common interest, including in Bulgaria, Greece, Romania, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, and Cyprus.

But what about the remaining Balkan nations? And what about other fossil fuels?

The European Union could well benefit from their resources, while them gaining a solid cluster of customer partners. This common-sensical approach must not be sacrificed in the altar of climate change radicals. Meanwhile, in a now well-known 4 November 2022 interview with Politico, Commissioner Breton has rather cynically proclaimed that combustion vehicles will continue to be sold by the Union to Africa for many decades.

Indeed, with regards to cars, is it reasonable to dedicate hundreds of billions of euro to phase out petrol by 2035?

Of course, we understand that the German politician has a difficulty in recognising that her 2030 objectives will not be met and she wants to minimise the risk of damage to her image. Nevertheless, that does not justify the inefficient assignation of taxpayers’ money and the condemnation of future generations up to 2050 to energy poverty. Including in the Balkans.

Neither does it justify the closing of energy production companies, simply because their output is considered to be dirty by the white-collar bureaucrats of Brussels and their subsidised minions.

Major investments certainly need to be put in place in order to gradually replace outdated technology. For example, the World Bank estimates that Bosnia and Herzegovina’s energy sector requires investments of more than $6 billion for modernisation, life extension and new generation facilities for renewable energy production sectors. Similarly, North Macedonia can significantly improve its grid electricity’s energy efficiency, where losses range from 14 to 16% of gross national electricity consumption.

However, such technology should not be reduced to green energy. Countries like Montenegro require a technological boost to explore and produce oil and gas, rather than suffering a border carbon tax imposed by Brussels. On the other hand, the government of Kosovo has shown deep reservations to extending the gas pipeline between northern Greece and North Macedonia across the border between North Macedonia and Kosovo; but is open to the idea – let us show them the way.

On the other hand, nuclear, recently reclassified by the Von der Leyen team as acceptable, accounts for 44% of total energy production in Bulgaria, 33% in Slovenia, 20% in Romania and 17% in Croatia.

A further priority is minimising institutional corruption, while promoting real competition, and avoiding monopoly in supply and commercialisation, towards a scenario of regulation reduction.

Even some mainstream members of the European Parliament, like Mr. Christian Ehler during the Strasbourg January plenary session, are already publicly airing the grandeur delirium of Von der Leyen’s plan, supported by the left-wing groups headed by the Greens. A prudent conservative line would concur to such criticism on the unrealistic terms of the euro-climate dream.

Source of the image: Bankwatch

Subscribe

Subscribe