On 16 September 2022, the European Commission published its proposal for a regulation establishing a common framework for media services in the internal market (European Media Freedom Act). The European Union institutions thus intervene in the media sector, which is known for its double nature of cultural and economic components.

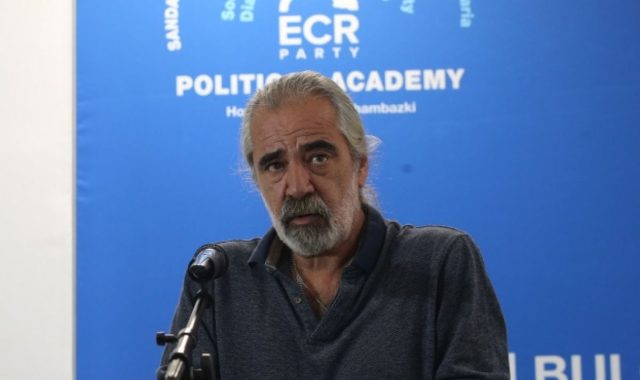

The proposal, accompanied by a recommendation on internal safeguards for editorial independence and ownership transparency of media service providers, is currently being discussed at the European Parliament’s committee on Culture and Education. The ECR shadow rapporteur is Mr. Andrey Slabakov (see picture).

The aim for this new legislative instrument is to guarantee media freedom and pluralism, in a context of advancing convergence of media service providers, new distribution technologies, new players and new possibilities of consumption of content.

Four Member States (Denmark, France, Germany and Hungary) have addressed reasoned opinions to the European Commission claiming that the draft Act constitutes a violation of the principle of subsidiarity. Furthermore, several other Member States (including the Czech Republic, Italy, the Netherlands and Poland) have expressed reservations.

Article 3 in the proposal deals with rights of recipients of media services, namely, the right to receive a plurality of news and current affairs content, as a concretisation of the fundamental right to freedom of information. However, one could doubt whether the right to have access to quality media is assured by a plurality of information sources.

Article 4 proclaims the rights of media service providers. In order to be independent, their editorial freedom needs to be respected by Member States. The latter must not interfere in or try to influence in any way, directly or indirectly, editorial policies and decisions of media service providers.

Such prohibition of interference on behalf of public authorities includes actions by the national regulatory bodies which are in charge of supervising the media, albeit not for the sake of hindering the work of journalists.

This protection of the journalistic activity is granted in view of the role of media as public watchdog in democratic societies. It could be added that journalists should contribute to the common good by transmitting and spreading truth.

In particular, Member States shall not detain, sanction, intercept, subject to surveillance or search and seizure, or inspect media service providers in order to find information about a source which the provider refuses to disclose. The protection extends to the provider’s family members, employees (and their family), and to both corporate and private premises.

Member States shall further refrain from deploying spyware in any device or machine used by media service providers, except for reasons of national security or serious crimes investigations.

As a complementary side to rights, Article 6 describes the duties of news media providers, which are necessary and important given the relevance and trust that these market actors have for the whole of society.

First of all, it is key for recipients to know who owns and stands behind news media. For this reason, national regulatory authorities keep an online media ownership database. Some argue that this should not be limited to the narrow framework of news and current affairs, but should also be extended to even purely entertainment and mixed formats.

Second, media service providers should guarantee the independence of their own editorial decisions. Corporate independence is assured when editors are free to take individual editorial decisions in the exercise of their professional activity. The corporate owner has the right and duty to define the overall line of the media service, after which it is the editors (typically an editor-in-chief) who decide on the publication of individual content items.

With regards to public service media, an expectation of quality information and impartial media coverage justifies a specific dedication in the Act. Political independence needs to be assured in media operators which, due to their stately nature, are particularly exposed to the risk of interference by States. Here, independence of governing bodies within public service media need to be safeguarded through procedural guarantees for the appointment and potential dismissal of executives. Terms of office need to be sufficient, as well as financial resources, in order to minimise pressure. A multi-year financing is considered ideal to keep providers out of political pressure.

Section 5 of Chapter III of the draft Act deals with the well-functioning of media markets, including rules on media market concentrations and mergers, media ownership and licensing and notification requirements.

Article 17 focuses on the protection of editorial content by media service providers on very large online platforms. Such platform providers are more constrained in the way they can moderate the content uploaded onto them. For example, such limitation can take place if the content is incompatible with the terms and conditions of the platform. However, if the platform provider intends to suspend its service in relation to a certain content, there needs to be a communication statement including the reasons accompanying the decision, plus the opening of an eventual “meaningful” dialogue between both parties and the possibility to substantiate the conflict via judicial review.

As oversight for the compliance with rights and obligations, national media regulators are vested with the responsibility of monitoring media pluralism, but also cultural and linguistic diversity, consumer protection, accessibility, non-discrimination, the proper functioning of the internal market and the promotion of fair competition. Here again, their independence requires fair and transparent conditions and procedures for the appointment and dismissal of their head and members.

In addition to the national layer, a so-called European Board for Media Services is created as a supranational cooperation body. This independent advisory body at Union level coordinates action of national regulatory authorities. Each of them will have one vote in the Board; this will be represented by a Chair, elected among the members by a two-thirds majority for a term of two years. The European Commission is represented through one person in the Board, but with no voting right.

Furthermore, the European Commission is granted a role of monitoring the internal market for media services and can issue opinions and guidelines. It is important to assure that the principle of subsidiarity is respected, given Member States’ cultural competence as proclaimed by Article 167 TFEU.

Finally, the draft Act addresses the issue of non-EU providers, particularly in order to combat disinformation. In the context of the war between Russia and Ukraine, the European Board for Media Services and the European Commission will coordinate measures by national regulatory authorities for the sake of public security and defense.

Subscribe

Subscribe