It is instructive to read the Parable of the Good Samaritan closely …

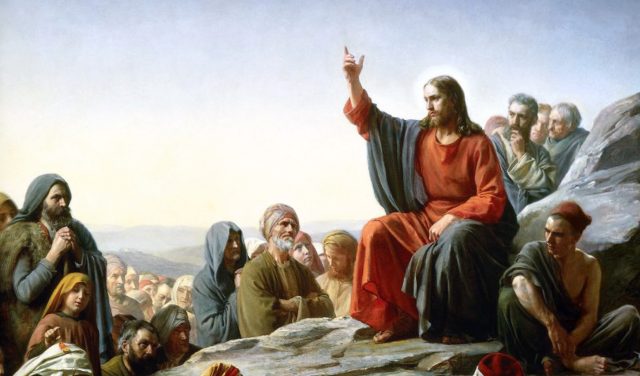

The holidays are an appropriate time in which to reflect on our Christian heritage. It is often said that it is incompatible with capitalism. I disagree, not only because historically they have coincided. Recall that Christ’s message was: ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’ It does not mean that you have to love your neighbour as much as yourself, although it certainly means that you should at least love yourself as much as your neighbour. A mother usually loves her child more than other children; it becomes an extension of her self. There is nothing wrong with that. Fortunately, not many mothers are like Dickens’ Mrs. Jellyby who neglected her own children because she was obsessed with projects in Africa. I would rather interpret Christ’s message as an exhortation to us to recognise all other human beings as members of the same moral community. It is a restatement of the reciprocity principle: ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’ It is not a demand that we should be forced to sacrifice ourselves for others, against our will.

Doing Good at his Own Expense

This becomes clear when Christ is asked to elaborate on who our neighbour is. In response he tells the parable of the Good Samaritan:

A man was once on his way down from Jerusalem to Jericho and fell into the hands of bandits; they stripped him, beat him and then made off, leaving him half dead. Now a priest happened to be travelling down the same road, but when he saw the man, he passed by on the other side. In the same way a Levite who came to the place saw him, and passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan traveller who came on him was moved with compassion when he saw him. He went up to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring oil and wine on them. He then lifted him onto his own mount and took him to an inn and looked after him. Next day, he took out two denarii and handed them to the innkeeper and said, ‘Look after him, and on my way back I will make good any extra expense you have.’

It seems to me that there are at least six practical lessons to be learned from the parable.

First, the traveller from Jerusalem to Jericho fell among robbers. This means that it is necessary to maintain law and order, to protect honest citizens against robbers. We need strong, but also limited, government.

In the second place, both the priest and the Levite passed by the victim, as he lay helpless at the side of the road. Charity is not necessarily to be expected from the intellectuals. They love projects, not people.

Thirdly, the very presence of the priest and the Levite on the road showed that it was a common thoroughfare. The original victim was therefore not guilty of recklessness by taking it to Jericho. This was not a dark alley in a bad neighbourhood where you might have yourself to blame if you were assaulted.

Fourthly, the Samaritan who helped the traveller had the means to do so. It is a propitious fact that some people can afford to help others, without necessarily sacrificing themselves for them. Margaret Thatcher famously observed: ‘No-one would remember the Good Samaritan if he’d only had good intentions; he had money as well.’

Fifthly, the Samaritan helped the traveller of his own free will. He did good at his own expense, whereas modern socialists only seem ready to do good at the expense of others.

Sixthly, if you were robbed and left helpless and wounded at the side of a road, on the reciprocity principle you would like somebody to help you: the Samaritan might have been in the situation of the traveller, not the other way around. Charity is in his and your self-interest.

Capitalism Keeps Greed in Check

In the parable the Good Samaritan represents capitalism. It is a tale about private charity in an emergency, not about redistribution from the more productive individuals in society to the less productive. Again, the Bible does not say that money is the root of evil: it says that unchecked greed, or the love of money for its own sake, is the root of evil. It is not greed that motivates the typical entrepreneur or venture capitalist. It is their urge to innovate, invent, create and cultivate—be it works of art, a new alloy, or a thriving railroad company. They follow their calling.

One of the strongest arguments for capitalism is indeed that it keeps greed in check, directs it into relatively harmless channels, whereas under socialism unchecked greed found among the rulers can become very harmful to their subjects. As John Maynard Keynes said: ‘It is better that a man should tyrannise over his bank balance than over his fellow-citizens.’

In Christ’s parable of the Good Samaritan there are five characters, and today, alas, they have changed roles. The robbers are in control of the government bureaucracy, and with the support or acquiescence of the priest and the Levite they are robbing both the traveller and the Good Samaritan by imposing exorbitant taxes on them and interrupting trade between Jerusalem and Jericho.

Subscribe

Subscribe