No fistfights on the steps of the National Gallery of Modern Art before entering, and no polibibita to welcome guests, as envisioned in the “Manifesto of Futurist Cooking” written in 1932. “The Time of Futurism” is not strictly a Futurist exhibition but rather a showcase of 350 works—including paintings, sculptures, projects, films, and drawings—that offer a deep understanding of what the first Italian avant-garde of the 20th century truly was.

The exhibition, which opened in early December and runs until February 28, was strongly supported by former Italian Minister of Culture Gennaro Sangiuliano and carried forward by current Minister Alessandro Giuli. It highlights Italy’s significant role in shaping global avant-garde movements through Futurism. An unmissable opportunity for anyone visiting the Italian capital to discover who the Futurists were, what they achieved, and how their ideas continue to inspire creative visions today.

“The exhibition celebrates the innovative impact of the Futurist movement in Italy and across Europe. This showcase,” says Federico Mollicone, Chairman of the Culture Commission of the Chamber of Deputies, “will make history for the sheer number of works and international lenders. With Futurism, art becomes total, breaking free from the confines of the canvas to enter daily life and intersect with a world where ‘everything moves, everything runs, everything changes rapidly.’”

The journey begins with the front page of the French newspaper Le Figaro, where, on February 20, 1909, the movement’s manifesto was published under the title “Le Futurisme”. Marinetti managed to secure its publication through cunning: he fell in love—or rather pretended to fall in love—with the daughter of the newspaper’s co-owner, a wealthy Egyptian. The manifesto’s eleven points exalt love of danger, rebellion as an essential element of poetry, and include more controversial ideas, such as disdain for women. These pages prioritize the racing car over the Winged Victory of Samothrace. Speed, speed, speed becomes synonymous with the future, aiming to destroy museums, libraries, and academies, which are viewed as symbols of the past. Appropriately, alongside the manifesto in the same room is a fiery red Maserati, the quintessential symbol of the movement’s early phase.

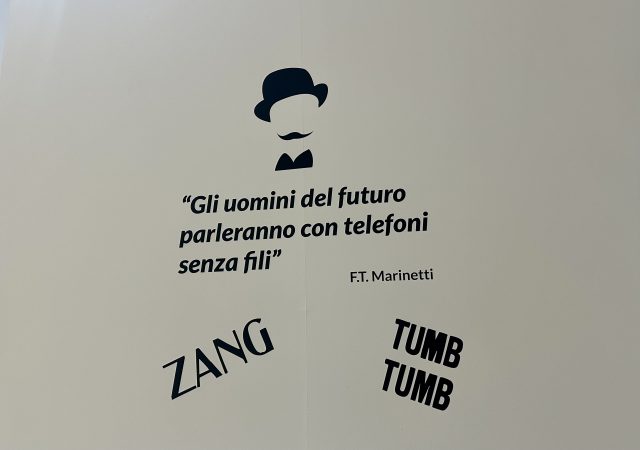

But the exhibition goes beyond manifestos to explain the essence of Futurism. It is primarily about images and paintings. Giacomo Balla’s “The Arc Lamp” pays homage to the manifesto “Let’s Kill the Moonlight”: a streetlamp illuminating the night more intensely than the moon itself. Visitors can also admire the portrait of Marinetti, titled “Soleil”, created by Futurist artist Rougena Zatkova, and a tribute to Marconi with his inventions, symbolizing the desire to transform human daily life. “Many literary figures of the time looked elsewhere, relegating industrialization to the background, while the Futurists,” explains Mollicone, “were the only ones to grasp that epochal moment. Today, following their example, and in light of the fourth revolution—the digital one—we must face new challenges to manage them and make them a resource for humanity and the future.”

The GNAM transforms into a hangar housing a large red seaplane and 350 works from around the world. Among the paintings evoking the sky and heroism, Tullio Crali’s “Before the Parachute Opens” stands out. Alongside celebrated artists like Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni, lesser-known figures such as Fortunato Depero are rediscovered. Literary manifestos blend with paintings, progress intertwines with preservation, and advertising becomes a means of societal penetration.

“We will invent together what I call wireless imagination […] To achieve this, one must give up being understood. Being understood is unnecessary. We’ve done without it, after all…” wrote Marinetti. He was right. The Futurists gave up being understood but never ceased to be remembered. Their legacy, full of contradictions and genius, remains central to debates on modernity and the ever-changing nature of art.

Subscribe

Subscribe