With such a provoking title did the Mathias Corvinus Collegium (MCC) organise a debate at the Liszt Institute Brussels on 27 June 2024. The event was hosted, ahead of the Hungarian Presidency of the European Union Council, by H.E. Dr. Tamás Iván Kovács, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Hungary in Belgium and Luxembourg.

Dr. Kovács recalled that inside the Liszt Institute one can still admire a part of the medieval wall of Brussels. He also praised the Hungarian glass work currently exhibited in the Institute by artists such as Endre Gaál, László Lukácsi, Marta Edöcs, Anita Darabos, Péter Borkovics, Kyra László, Kristóf Bihari, Balázs Sipos, Eszter Bősze, and Amala Gyöngyvér Varga. Furthernore, he announced the visit of Dr. Tamás Sulyok, President of the Republic of Hungary on 1 July. One day later, the celebration of the Hungarian Day will take place at the Parc du Cinquantenaire, including a Rubik’s Cube competition, Hungarian Dog Breeds, plus music and dance.

Ambassador Kovács brought to mind his university studies of Roman law and the proverb de gustibus non est disputandum, in order to show how some dictatorships have defined beauty in order to instrumentalise it. But, at the same time, he acknowledged a certain objective viewpoint, art being a reflection on our environment – either intentional or unintentional.

In Ancient Greece, art would not only express matter, but also thoughts, feelings and character. According to Socrates, we say that something is beautiful if it achieves its end. More relativistically, Kant broke the relationship between beauty, on the one side, and perfection or moral good on the other, so that art became autonomous and subjective. The Ambasssador made a point in saying that this helps understanding what is happening now.

MCC Executive Director Prof. Frank Füredi took the floor to present the discussion on the artistic legacy of Europe. According to Prof. Füredi, art and beauty must not be relegated just to museums; people’s artistic sensibility needs to be nourished and educated, to create a certain sense of taste. On the other hand, this must not lead to instrumentalising art, as it is the case by the EU to distribute its propaganda.

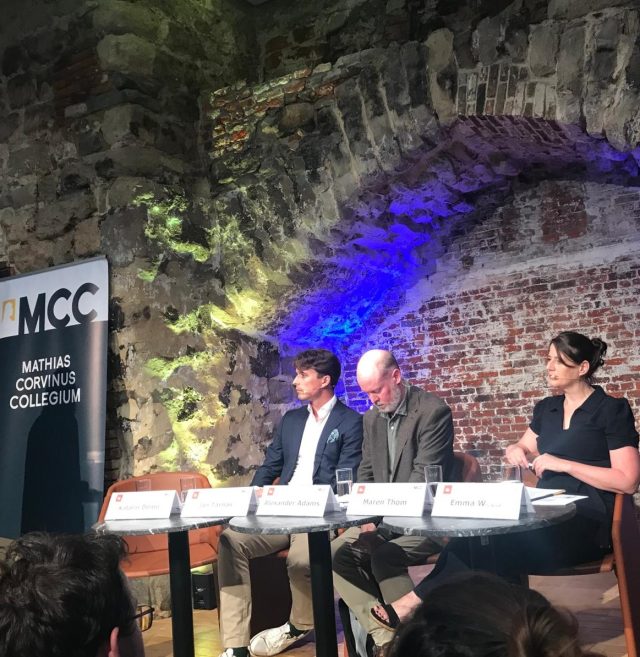

A panel discussion was conducted by Dr. Katalin Deme, who asked the other participants what the meaning of art in our century should be, if we want to preserve our civilisation. Prof. Jan Tarnas, of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, summarised the philosophical problem of beauty as a debate between realism and idealism.

A traditional account of beauty would tend to focus on the beauty of a thing in itself, the artist having aimed at perfection from the perspective of nature. Art produced beautiful objects for contemplation. The best definition, according to Prof. Tarnas, has been provided by Saint Thomas Aquinas, who wrote that art imitates nature and fills its gaps. This realistic conception of art demonstrates truth, denies relativism and compensates for ugliness in the world.

Its goals are inner and harmonious coherence and external guidance of the human being towards the realisation of his potential.

The idealistic vision is that of an imaginary phantom where creativity is the primary means for producing art. Absolute freedom becomes a slogan of this modern artistic ideology. Such creativity and freedom are the principles invoked by relativist and post-modern philosophers to separate art from beauty.

However, the product of such ideology, according to Prof. Tarnas, is an anti-art with a negative impact on civilisation and on the place of the human being therein. Certain new tastes are created by an expert community to extend madness, depravity and a “civilisation of death” as a means of social engineering.

UK artist, art critic and poet Mr. Alexander Adams has defended classical beauty, the natural order, the preservation of craft and the authors’ independence from the State. However, at the same time he believes that the role of an artist cannot be the imitation of other artists.

Rather, the artist should describe the world he lives in, with unique forms of place and time. An example of such endeavour in the past would be Degas, who would portray his famous ballerina with a face described at this time as that of a monkey, and other Degas women position being qualified as “animalesque”.

MCC Senior Research Fellow Dr. Maren Thom ascribed herself to the idealistic view of art. In her opinion, beauty links people one another. As a film critic, she chose Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane” to show that art allows man to replicate God’s ability to create beauty, particularly at moments that could be called “holy” or “sublime” thanks to their unique blend of emotions in space and time.

Art is something that transcends us, something greater than us, as Kant would put it in his Critique of Judgment; for Hegel it is feeling the Universal, as fans would share a moment of interpersonal connection in a football stadium.

However, Prof. Thom added that this discussion about the sublime seems outdated and replaced by “vibes”, a vocabulary expressing a new focus where beauty is absent. In cinema, vibe is considered to be an emotional affect of images relating to previous affects. Whereas classical cinema used to tell stories, now it is more an experience that needs to be expressed artistically. The recent UK film “Saltburn” embodies this approach.

More from a Christian than from an idealistic conception of art, fourth panellist Emma Webb of the Common Sense Society UK agreed that beneath the art discussion lies a discussion between Christian metaphysics and Hegelian metaphysics.

An example of the latter is the recent controversy about Jonathan Yeo’s portrait of King Charles III. Supposedly, the fact that this painting has created a public reaction shows its success: Art should create a conversation, that is in essence what defines art.

On the contrary, Christian metaphysics show an ordered universe created by the Divine Providence, an objective basis that has produced works such as Michelangelo’s frescoes on the Vatican’s Sixtine Chapel.

The dialectical definition of art defended by Hegelian metaphysics ends up with Marcel Duchamp’s porcelain urinal fountain. Critical theorists such as Herbert Marcuse defend that art should be deprived of beauty, both of which need desecration. As James Lindsay has brilliantly explained in his series of podcasts, Marcuse and other members of the Frankfurt School support a dialectical process in history where we go beyond the liberal tolerance, which would only perpetuate the conservative order and “dress intolerance”, towards a positive liberation in order to stand against our history of oppression.

We now live in this logic. Anything can be art, as long as it serves the progressive causes; they actively repudiate beauty and place ugliness in beauty’s place to serve political means. But of course, something in us tells us that that is only pseudo-art, subversion and destruction.

In fact, the Hegelian dialectic swallows itself. What was once liberating becomes oppressive in the deployment of history. For example, Hogarth’s criticism of his time is now portrayed as colonialist and enslaving; Virginia Woolf’s books are now printed with warnings issued by the woke movement.

Mobs vandalise statues in the UK, and art vandalism is in itself considered art, in fidelity to the March of the Dialectic.

Subscribe

Subscribe