We have only two friends around here. The Serbs and the Black Sea. – Old Romanian Proverb

For many centuries, the Balkans have maintained a reputation as the “powder keg” of Europe. Whether it was due to ethnic and religious diversity, territorial disputes, external influences or simply the historical fragility of some states that emerged in this area, the geographical zone has been deeply shaped by conflict. And while conflict ends, mistrust and damaged relations remain and perpetuate to future generations that learn about the past.

But so does cooperation, and a mutual effort to preserve peace between two peoples. It is such examples that remind us of the realpolitik advantages of actually playing fair (not just pretending), and of being a good neighbor. Since the inception of their modern stately forms, Romania and Serbia are the only neighboring Balkan nations that have never seen armed conflict between one another.

One should not get the wrong impression. Tensions, as always, have existed. Especially due to the influence of foreign, stronger actors. But a collaboration that span over more than 600 years is worth analyzing, especially due to the effects it has, even today, on the mutually shared good perception of each other that the two peoples posess. Let us look at the defining moments that formed this bond.

Resisting the Empire

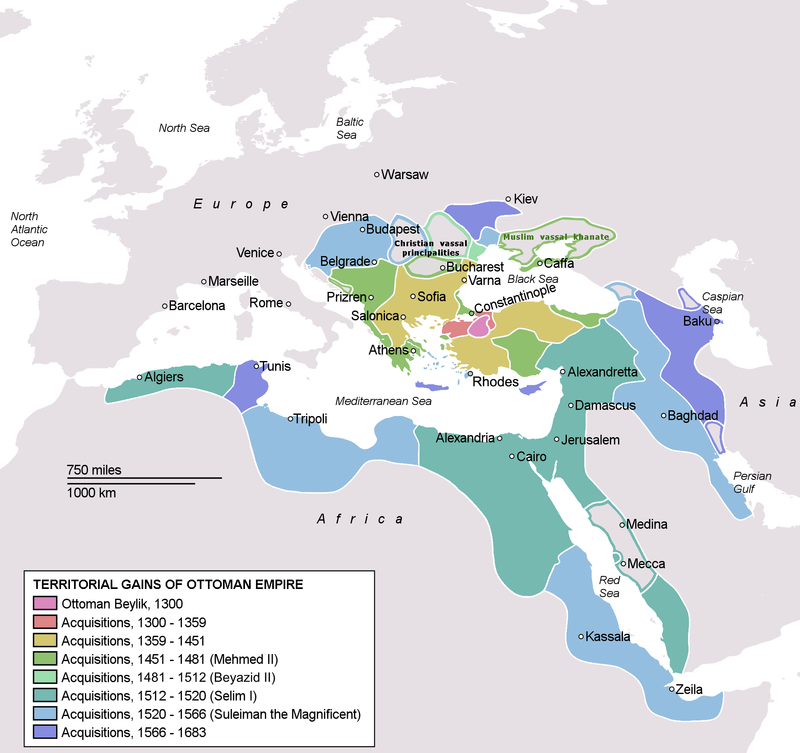

Throughout history, Romania (comprising the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia) and Serbia found themselves at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, facing the common threat of Ottoman expansion. In the face of this formidably aggressive adversary, both nations recognized the need for strategic collaboration to defend their territories and peoples. Historical records reveal several instances of Romanian-Serb cooperation to counter Ottoman expansion, demonstrating the significance of their joint efforts and learning each other’s defensive tactics.

The 14th and 15th centuries were crucial periods when Wallachia, Moldavia, and Serbia came under the expanding influence of the Ottoman Empire. Both Wallachia and Moldavia were vassal states, while Serbia experienced direct occupation. Despite their differing political statuses, the three regions shared a common aspiration to preserve their autonomy and resist Ottoman encroachment.

In the late 15th century, the reign of Vlad Țepeș “the Impaler” in Wallachia saw further Romanian-Serb cooperation against Ottoman rule. Vlad fostered diplomatic ties with Serbia and Hungary to counter Ottoman ambitions in the region. And while their efforts failed, both Wallachia and Serbia entering the 16th century under the grip of the empire (one as a vassal and the other under direct occupation), the mutual desire for independence and sovereignty generated solidarity between the two peoples.

Haidouks

The early 16th century witnessed the emergence of haidouk bands in both Wallachia and Serbia. These bands were decentralized and composed of outlaws and rebels who resisted Ottoman authority through guerrilla warfare. The haidouks often found refuge in the mountainous and remote areas that straddled the borders between Romania and Serbia. These regions provided a natural hiding place and sanctuary where haidouks from both sides could establish contact, exchange information, and plan common actions against the enemy.

In some instances, haidouk leaders from Romania and Serbia would coordinate their efforts and engage in joint operations against Ottoman forces and officials. This collaboration allowed them to combine their strengths, information and resources, making it more challenging for the Ottoman Empire to suppress their activities effectively.

During these times of resistance, a mutual hero figure arose. Starina Novac (most commonly known as “Baba Novac” – “the old one”) was a legendary haidouk, and holds a significant place in the folklore and historical memory of both Serbs and Romanians. Novac was a charismatic and daring figure who became a symbol of resistance against Ottoman rule.

For both peoples, Baba Novac is regarded as a hero due to his fearless and unwavering commitment to the fight for freedom and justice. He led a band that transcended ethnic and national boundaries, comprising both Serbs and Romanians. His audacious raids on Ottoman caravans and tax collectors made him a legendary figure, representing the common people’s defiance against the Empire’s tyranny.

The tales of Baba Novac’s heroism and cunning have been passed down through generations, becoming an integral part of the cultural heritage of both Serbs and Romanians. Today, he continues to be revered as a symbol of bravery and resistance against oppression in both countries, having monuments erected to him, and streets or neighborhoods that wear his name.

The Little Entente & The Second World War

Romania and Serbia endured hardship but managed to enter the 20th century as independent kingdoms. The ascension of King Alexander I to the Yugoslav throne in 1921 proved to be a turning point in Serbian foreign policy. He sought to build a strong relation with Romania, to counter Hungary’s irredentist aspirations that were targeting both states. Together with Czechoslovakia, the two states set up a strong defensive alliance that would last until 1938. By forming a united front, the member countries sought to deter any potential aggression from Hungary and safeguard their interests. The Little Entente was a significant diplomatic initiative to promote regional security and foster cooperation among the member states, aiming to maintain peace and stability in the volatile Balkans.

In 1940, Romania was forced to cede several territories to neighboring countries, including parts of Northern Transylvania to Hungary and Bessarabia (today part of Moldova) and Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union. These territorial losses were significant blows to Romania’s territorial integrity and constituted the main reason the country entered the Second World War on the side of the Axis.

As the war progressed, Nazi Germany (at that time allied to Romania, but belligerent to the Serbs) invaded and occupied Yugoslavia in 1941. During the occupation, the Germans sought to expand their influence and strengthen Romania’s collaboration by offering some of the previously lost Serbian territories to Romania as a reward. However, Romania refused the offer, maintaining that they did not wish to receive territories taken from another sovereign nation.

Despite their alliance with Hitler and The Reich, Romania’s refusal to accept the Serbian territories demonstrated a degree of restraint and an unwillingness to engage in further territorial expansion at the expense of their neighbor. The decision is still regarded as one of the strongest pillars of the mutual Romanian – Serb respect.

Defying the Bloc

Diplomatic and cultural relations hit another all-time high during the late 1960’s and 1970’s. Romania, under the leadership of Nicolae Ceaușescu, pursued an independent foreign policy during the Cold War, often diverging from the positions of other Eastern Bloc countries aligned with the Soviet Union. Ceaușescu’s political quest for sovereignty and autonomy in international affairs ultimately led to tensions with the USSR and other Warsaw Pact members. This was seen as positive by Yugoslav leader, Josip Broz Tito, who championed the Non-Aligned Movement, promoting a policy of neutrality and cooperation with both the Western and Eastern blocs. Naturally, relationships improved.

But aside from the diplomatic aspect, the cooperation between average citizens (especially those near the mutual Romanian – Serb border) increased. Yugoslavia had access to the Western markets, and Romanians had the desire for such products. Black markets and contraband represented the foundation on which, once again, the two peoples were offering each other a helping hand. Even today, most Romanians who lived their young years under communism can safely attest to the fact that their first pair of blue jeans or their first Abba audio tape was from someone who had a Serb friend fairly close to the border.

On a more serious note, Serb groups helped Romanian dissidents escape the wrath of Ceausescu (that would result in many years of imprisonment and hard labor), usually with a boat over the Danube. Due to positive diplomatic relations, border security had been systematically decreased over the years, granting escapees a better chance of not being spotted or caught. Once arrived on Serbian territory, the locals would (for a fair sum of money) transport the fleeing Romanians to the gates of the Western Bloc, Austria.

The Separation & The Reunion (?)

In 1999, Romania was on the verge of joining NATO, while on the other side of the border, the Kosovo War was going on. The Romanian government believed that NATO’s intervention would help bring an end to the violence and restore stability in the region, so it allowed passage for bombing campaigns on Serbian soil. A significant number of Romanians protested the decision, claiming it could bring damage to the relations their nations cultivated through so many centuries, but the government at that time decided that the risk of being excluded from a potential NATO membership was just too high to not conform.

Relations were temporarily damaged, but both populations seemed rather understanding of the realpolitik implications of the decision, with no axe to grind remaining between them after the finalization of the conflict and the arrest of Slobodan Milošević. Moreover, Romania refused to recognize the independence of Kosovo, one of the reasons being cited by former heads of state being the special relation with the Serbs (who officially consider it a part of their territory).

As of today, Romania and Serbia have formal agreements in various fields, indicating good cooperation and bilateral relations between the two countries. These agreements cover areas such as trade, economy, culture, education, tourism, and defense. Diplomatic visits and high-level meetings have also taken place, demonstrating a commitment to preserving ties and addressing shared challenges.

And while relations have not always been perfect, the mutual aid offered over so many centuries is a solid foundation for trust and respect, which is also transposed in the cordial attitude Serb and Romanian citizens have towards one another. Recent news about Serbia as a potential EU member state in the future have been well received by institutions, the press and the population of Romania.

Subscribe

Subscribe