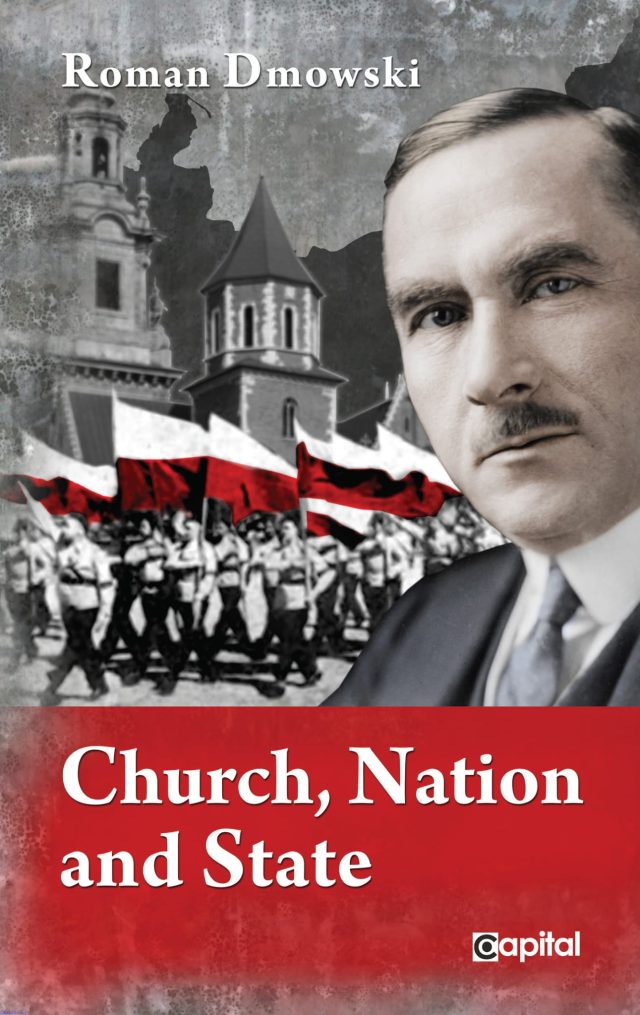

The Polish conservative statesman Roman Dmowski, to whom Poland owes its current independence to a great extent, wrote his essay “Church, Nation and State” in 1927. The text is divided into five chapters of a similar length.

In the first, the author defends that the freemason tradition started in the eighteenth century was coming to an end in his time. French, English and American freemasons aimed at destroying religion (particularly Roman Catholic) in order to free the individual, but also, according to Dmowski, defenders of religion had an erroneous understanding of their duty.

The freemason strategy has been to instill religious apathy, which triggers a fundamental significance for a nation, as its individuals become materialistic, drag through life without a clear objective or any strong belief, let alone any sacrifice of their egoism. Furthermore, the religious tradition is broken and so will not be passed along the nation’s next generations.

The second chapter delves into the difference between Catholic and Protestant nations. However, Dr. Dmowski begins by describing the modern nation, as a continuation of the classical nations fostered by Christianity and the Roman Church under a single faith.

In the specific case of Poland, our author defends that it was not values but coercion by the state in cooperation with the Church that bound pre-Christian tribes together. After centuries of work, strong families were forged. The reference to families in the fabric of a nation is both very interesting as well as very classical.

His reference to the Protestant Reformation also deserves notice. Because such religious revolution lead to fragmentation, the only way to keep unity was strengthening monarchical power. Prof. Dmowski’s does not mention him, but here we see Jean Bodin’s modern conception of sovereignty.

Other elements defining a nation’s essence are its ethnic roots, centuries of existence of the state, and common Faith.

At the time of Dmowski, but we could say so of today as well, Protestant nations are predominant, together with their economic system, capitalism. Liberation from Rome’s spiritual rule unleashed national egoism. Here, the Polish politologue sees a fracture with the concept of Christian nations developed in the Middle Ages.

The third chapter deals with the appearance of nationalism in Catholic nations by the end of the nineteenth century (Maurras in France, Corradini in Italy, Popławski in Poland). Dmowski explains that Catholics were caught between two alternatives: either refraining from defense against attacks by Protestants, as those of Bismarck on Poland, by exerting only a moral condamnation of such attacks – which amounts to cowardice; or else responding to Protestants’ national egoism with an analogous Catholic nations’ own egoism, though this entails a lack of respect for Christian principles.

Ten years later than Dmowski, Pope Benedict XV would condemn such concept of nation in his famous encyclical “Mit brennender Sorge”.

The fourth chapter explains the role of religion (i.e., of the Roman Church) in the life of nations and states. Dmowski reflects the liberal idea that the Church has to limit itself to teaching the Faith, but forgets about mixed matters in the temporal and secular orders, plus the duty of the state to follow the teaching of the Church, even in temporal and secular orders though without the Church actually deciding on these.

He does recognise that a “truly Catholic nation” must make sure that the laws and state institutions through which it operates are in accordance with Catholic values; but the classical concept of nation rather means that any nation must make sure that the laws and state institutions through which it operates are in accordance with the teaching of the Roman Church.

Government by the state populace (a term that Dmowski could replace by “national sovereignty”) results in a clash between groups of very diverse creeds, each of which had overtly clear goals and aspirations, wherefrom the organization of government and the politics of the state become the result of a struggle between organised forces and thus the state is no more a consistent agent which works in a particular direction for an extended period of time.

Beyond Dmowski, one could say that the modern state does not work in the direction of the common good.

Finally, the Polish intellectual explains what the politics of Poland as a Catholic country should be. He starts by defending freedom of creed, which is in contradiction with the classical view of the relationship between state and Church; but then he turns back to Ancient Rome and sees there a first nature for Poland, and a second nature in Catholicism.

Source of image: Wydawnictwo Capital

Subscribe

Subscribe