“Many young people are not xenophobic but their lives are precarious, say experts, amid crises in housing and healthcare”. So begins the latest article in The Guardian (heaven knows there are many) trying to explain the vote in the general elections that happened in the Netherlands last month. In particular, the victory of Geert Wilders and his political party. For the legacy media (or at least the most significant percent of it), each time an anti-open borders party wins, the title must include “populism” and the reasons for the victory must include many nuances, with the exception of the elephant in the room – immigration. Sometimes it’s the housing crisis, sometime its “Russian interference”. Sometimes it’s 4chan and “meme culture” combined with violent video games. Other times it’s the economy. It’s “a rejection of the rich elites”, or “a vote against social measures for the poor”. But it’s never, never ever, immigration. At least not for so many of them.

However, for the European citizen, things look different. And even the official public perception organism of the Union goes to show it. According to Eurobarometer, ever since 2017, the main and utmost concern of the European citizen has been immigration, the open borders policy that was not very much debated, but rather very much imposed at the start of the Islamic migration crisis in 2015-2016. Since that point, 58% of EU citizens believe “integration” failed (Nota bene: the European Commission doesn’t present it that way. It boasts that “42% believe it was a success”. The power of wording…). To this day, immigration remains the most powerful issue besides the war in Ukraine and the inflation connected to it since its inception. It’s not rocket science, it’s a simple statistical fact. People are concerned about two main things. One is besides the borders of the European Union (so the power to modify the fiber of reality via political action is relatively low), and one is <at> the borders of the Union and inside them. That is immigration.

So, why the discrepancy in presentation? Let me not be misunderstood: healthcare, the price of housing, the economy and other issues are, indeed, very important. Nonetheless, the “spine” of the “populist” ascension remains what it always was. Immigration. Mass immigration. By downplaying its importance, the legacy media attempts to make the European citizen forget that in 2015, at the start of it all, there were people, people with names and surnames, people who belong to certain political parties… that encouraged the phenomena.

Sometimes, when this fact becomes too pointy, the media actors that support the established political parties attempt to promote a worldview in which the rejection of Islamic (and some African-descent) migrants is due to some form of fervent ethno-nationalism. A large chunk of population is displayed as simply being inherently racist. And while there, indeed, are some fringe organizations and persons who promote racism across Europe, their numbers are probably at historic lows.

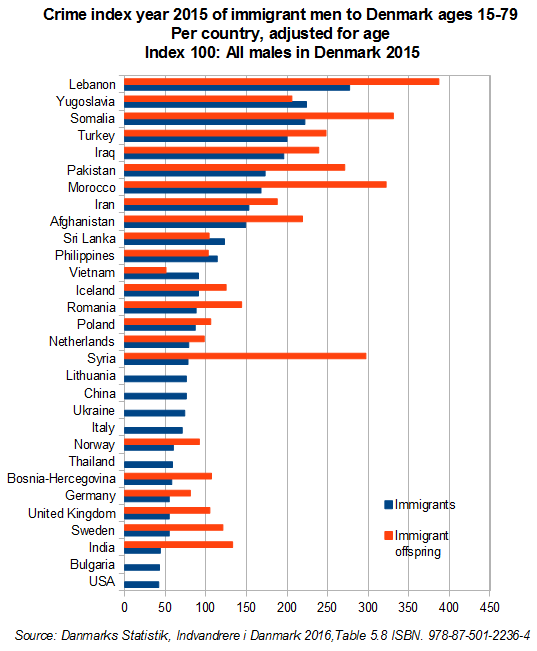

If you ask the everyday supporter of a stricter migration policy (and/or relocation), the main motives quoted for this stance would be criminality and enclavisation. And, at least statistically, they are right. This is no longer a perception issue, as it was when the first waves of undocumented migrants started pouring into the old continent. A large consensus among those who monitor criminality exists that Islamic migration bolsters the phenomena heavily.

In 2017, 74,4% of thefts in Germany had migrant perpetrators. 37% of all rapes and 30% of the murders were also attributed to migrants. An even more disturbing study done by the national television of Sweden in 2018 revealed that over 58% of convicted rapists were non-citizens. In Denmark, criminality by ethnicity has been documented even more profusely, and the results show that out the top 10 most convicted-for-felonies ethnicities, 8 are from Muslim countries. And this enumeration could be much longer, but that is not the point.

Interviewed by France24, political consultant Johannes Hillje, who is also the author of an unremarkable (it has not even been translated) “Propaganda 4.0: how far-right populists do politics” expressed disappointment in the fact that VVD (Mark Rutte’s center-right party) “had no power to set the terms of debate on Wilders’ preferred themes”.

With all due respect to Wilders, this is an unrefined overestimation of his political prowess. The aspects that the legacy media try to put forth, sometimes through the voices of campaigners and consultants, have a much simpler explanation, really. It was not Wilders who set the tone of the debate for the elections in the Netherlands. It was society. Wilders only sold the right size of shoe for the foot’s length. He did not set the length. In 2018 after the great waves of migrants that arrived from Islamic countries, 39% of the Dutch were firmly for reducing or stopping the phenomena all together. In the previous year, Wilders scored a modest 13% in elections. Recent polls on the views of the Dutch are hard to come by, since entities that would fund such research are also scarce. But a logical correlation would say Wilders captured 1/3 of the anti-immigration vote back then. The same 1/3 now (25% in the 2023 general elections) would mean that 75% of the country is opposing the phenomena.

To this, the cosmopolite and wise (at least in their own perception) centrists or left-leaning intellectuals would argue that the only thing that increased is the populist ability to tap into the percentage of citizens that oppose migration. But that couldn’t be a grosser example of cognitive gymnastics. Such a statement can’t be made anymore, since most of the “mainstream parties” have, in the last year or two, adopted (with a debatable amount of perfidy) an anti-immigration stance in their politics. Just look at how the EPP is trying to emulate the rhetoric through the voice of Manfred Weber, who seems genuine in his belief, and some of their national parties such as Forza Italia or the Popular Party of Spain. Even some parties on the left are now against open borders, rhetorically, at least. The Overton window has shifted.

But with such a rich offer for the anti-immigration voter, who now finds himself in the majority at EU levels, why vote “populist”? Here I possess two answers. One is an inevitable factor, and the other is related to perceptual authenticity. First of all, “mainstream parties” are experiencing the peak of what we can define as an erosion of trust.

Citizens, once hopeful and receptive to the pledges made during election campaigns, now view these assurances with a skeptical eye. Several factors contribute to this pervasive distrust, shaping a disillusioned electorate that questions the sincerity and feasibility of political promises.

One primary reason for the skepticism lies in the historical track record of unfulfilled pledges. Over the years, citizens have witnessed a pattern of politicians making grand promises during campaigns, only to fall short in their delivery once in office. Whether it be unmet economic targets, failed social reforms, or unaddressed environmental concerns, citizens have become accustomed to a widening gap between rhetoric and reality. This recurrent theme has bred cynicism, prompting voters to question the genuine commitment of politicians to their stated objectives (as they should, actually).

Moreover, the advent of social media and instant communication has exposed the behind-the-scenes machinations of political campaigns. Citizens now have unprecedented access to real-time information, enabling them to scrutinize every move and statement made by politicians. This heightened transparency humanizes, but also knocks off the pedestal figures that could be sold by the legacy media as providential saviors. The free market of saviors is freer than ever.

And here comes in the allure of authenticity. One significant aspect of “populist” appeal lies in the straightforward and unfiltered communication style adopted by these candidates. Unlike their mainstream counterparts, these characters are often perceived as speaking directly to the concerns of everyday citizens, employing language that is relatable and devoid of the political jargon that can distance politicians from the public. This authenticity in communication fosters a sense of connection, making promises appear more genuine and attuned to the realities faced by the electorate.

It also does not help the established political parties (especially in Western Europe where the phenomena hit the hardest) that there are palpable examples in the Union (and around) of strong-style handling of the issue. One needs to look no further than Law and Justice in Poland and (despite his many flaws) Viktor Orbán in Hungary. Their decisions to heavily enforce the borders and become, to a certain extent, radical on strict control has payed dividends. Boris Johnson’s bold Rwanda resettling plan (that truth be told was a lot more humane than some newspapers presented it) was a popular measure between British conservatives.

So yes, Manfred Weber is right. The established political parties have to come to terms with the fact that we can no longer delay a real solution to the mass immigration problem. Otherwise, the pillars that held them up high until now will slowly but surely erode under the waters of what they and their advocates in the press define as “populism”. The only problem Weber has is that the EPP won’t really listen to him. But that is a story for another time.

Subscribe

Subscribe