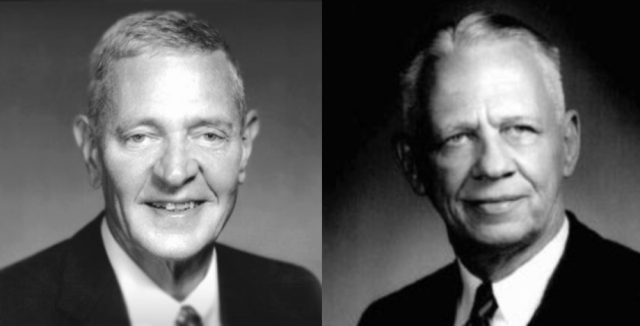

With that very same title did Willmoore Kendall publish an article, together with George W. Carey, in 1964 (Journal of Politics, vol. 26). Exactly six decades later, the theme appears as relevant, given the surge in conservative movements across Europe; moreover, the anniversary seems an excellent way to start the new year.

The text was structured in an introduction and four parts. The introduction recalls the various meanings the term “conservative” is frequently used to describe. For this reason, our authors avoid a rigid definition, though they defend the concept to be indispensable.

The first part articulates the basic human situation out of which the terms conservative and conservatism first arises. Individuals and groups interact in societies either competitively or cooperatively; this requires rules.

Over time, rules are inherited and become established. However, heritage does not impede change or innovation. Such change can be either unintended, long-term, almost imperceptible. Or it can be deliberate, in which case the group promoting such change is currently called “progressive”, “liberal”, “radical”, or “modernist”; while the group resisting such intended change is referred to as “conservative”.

The second part recognises, through various difficulties, that a more complex reality can exist and has actually existed throughout history as well as today. For instance, there might be different “conservatisms”, that is, multiple groups opposing deliberate change for different reasons each; and some might indeed be more relevant than others within a society. By way of example, we could reflect here on Christian conservatives, on one side, and Jewish conservatives, on the other.

Another difficulty can be perceived as arising from pure passage of time. Conservative ideas might incorporate only a recent heritage, thereby forgetting previous elements of that heritage. This again contributes to the multiplication of conservatisms. Both Kendall and Carey accept to denominate these different schools as conservative, but the degree of acceptance of liberalism in each of them clearly varies.

The third part -the longest of the four- focuses on the United States and UK politics, taking the conservatism of Edmund Burke as the standard or reference point.

Burke described six items of opposition between conservatives and progressives: (i) the former defend the principle of morality while the latter adhere to the principle of consent; (ii) the former defend the principle of hierarchy while the latter adhere to the principle of equality; (iii) the former defend that there is no general doctrine of the rights of man without a given political context and without duties, while the latter adhere to the doctrine of the rights of man; (iv) the former defend what Chesterton would later call the “democracy of the dead” while the latter adhere to the “democracy of the living”; (v) the former defend the principle of property while the latter adhere to the principle of redistribution; and (vi) the former defend the principle of true religion while the latter adhere to the principle of relativism or skepticism.

Commenting on Burke, Kendall and Carey see democratic suffrage as an intensification of control over government.

The United States case has its own specificities. The American tradition is embodied in three documents drafted by the Founding Fathers: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Federalist.

Yet the same Burkean criteria can be applied on the other side of the Atlantic. Diffusion of authority and the defense of intermediate institutions is a valid general rule for conservatives, in England, the US and overall. So is the resistance to egalitarianism, as well as free enterprise and less government intervention in the economic order, according to the tandem professors.

Finally, the fourth part concludes that the ultimate division between conservatives and progressives is equality. Therefore, an advance of egalitarianism marks a certain decline in conservative influence.

Source of image: Law & Liberty

Subscribe

Subscribe